Matsutake: or the parable of the elephant and the three blind men

From CTD researcher Catherina Wilson’s blog Rumours on the Ubangui

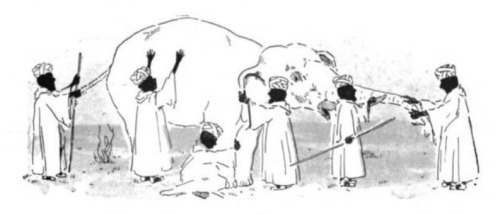

An old Indian parable relates the story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant. One day an elephant is brought to town and each of the men is asked to conceptualize and explain what the elephant is like by touching it. Each blind man feels a different part of the elephant body, but only one part. They then describe the elephant based on their (partial) experiences: for the man feeling at the tusk, the elephant is like a snake, for the one holding the foot, the elephant is like a tree stump, the one who touches its ear exclaims he is touching a sheath of leather, and so on… Even though their descriptions are partially right, they do not overlap. The blind men disagree and discussion arises as to what an elephant is. The moral of the parable is that people tend to project partial experiences as the whole truth, ignoring other people’s partial experiences.

One of the things that intrigues me the most when arriving in a new place, is the new constellation, in terms of networks and connections, one comes to discover. After spending a week in N’Djamena participating in the Connecting In Times of Duress (CTD) conference, we visited one of my colleagues, Souleymane, in his home town, Mongo, where we met his family. Mongo lies in the centre of Chad, about 500km East of N’Djamena, on the way to Sudan. It is in Mongo that I realized the extent of the ‘new’ constellation in which I found myself.

The nature on the way to, in and around Mongo is of an exceptional beauty. On the way there we passed herds of dromedaries, they are owned by the nomadic Arabs and they inevitably carry the winds of the Sahara on their humps. Yet we were in the Sahel. On Wednesday, market day, Souleymane took us to an impressive cattle market: .A male dominated market under the burning sun. I felt so rich, at least in terms of my work as an ‘Africanist’, how can you call yourself an Africanist if you have only experienced one type of Africa? Man and nature, the Sahel plains, its dromedaries were all new to me. Chad is a real natural jewel.

On Wednesday, market day, and in addition to the dromedaries, tall, robust trucks with huge tractor-like wheels, having left Libya and crossed the Sahara, bring manufactured goods, such as pasta, to sell in Mongo. Third quality pasta riding across the desert. Then there are the numerous, a little less sturdy, big 4×4 pick-ups from Sudan carrying, among other, Coca-Cola and oil. All of a sudden I was part of a world linked to Libya and Sudan. New constellations stretch and foster a nomadic mind-set. This is also Africa.

On the way to Mongo

Cattle market under the burning sun

In N’Djamena, too, I experienced a new, complimenting, perspective related to the mobility of the CAR (Central African Republic) refugees in the region of Central Africa. In the opening of the conference, Mirjam de Bruijn referred to the mobile margins of my research. I had studied the Central African community of refugees in Kinshasa, however, in only a couple of days I met a dozen of Central Africans in N’Djamena. Soon, N’Djamena turned out to be a mirror image of Kinshasa.

While in Kinshasa a majority of the refugees are Christian, in N’Djamena many of the CAR refugees are Muslim. While the refugees in Kinshasa had fled Bangui in mid-2013, just after the Seleka’s successful coup d’etat, those of N’Djamena fled at the end of 2013/beginning of 2014, when the anti-Balaka assaulted the capital city. While in DR Congo the refugee camps are in the North, along the border, in Chad they are in the South, also along the border. While from the point of view of the refugees in Kinshasa, the grass in Brazzaville seems greener, the refugees in N’Djamena search for opportunities in Cameroon. In my research, the Central African Republic juxtaposes and links Kinshasa to N’Djamena. I even met a couple of Banguissois who had started learning Lingala in N’Djamena, while they had never shown interest in this language before. New geographies, new constellations, new connections, new mind-sets.

This brings me back to the parable of the elephant. In our research the elephant stands as a metaphor for CAR and we, the researchers of the CTD team, are the enquiring blind (wo)men who touch only one part of it. For Adamou AmadouCAR is smooth, hard, long and pointy and it is related to Mbororo nomads who used to employ bow and arrow to defend themselves against road blocks in CAR. For Inge Butter, CAR is thick and sandy and stands synonym for the Arab women selling Sudanese spices in (the now infamous) 5 kilo market. For Souleymane Abdoulaye Adoum, CAR has an historical dimension and a variety of links to Southern Chad. In the Being Young In Times of Duress project, Jonna Both and I work together with a local research team in Bangui which is composed by people from the centre of the country, another part of the elephant, and which will undoubtedly give way to another, complementing, understanding of the country and the conflict. For me CAR is like the long, yet very soft and moveable trunk of the elephant. It meanders through the lush green forest, it is rich in fish and it is inseparable from the rumba sounds that travel up and down the river.

Contrarily to the blind men, we must communicate our own analysis, while listening to the experiences of the others. Inspired by ‘new forms of collaboration in cultural anthropology’ (380)[1], different experiences can add up to more holistic descriptions. Working together enables new forms of understanding and defies ‘the impulse of centralizing and totalizing knowledge production’ (399)[2]. As a team, we can make an attempt to understand CAR’s complex history, its multivalent violence and, especially, the polyphonic suffering of its people. This country, in the heart of the continent, finds its strength in its diversity, and the Central African people know it. If division strives, CAR will be doomed to suffer along the line of all its (politically fashioned) fissures, and there are many.

[1] Choy, Timothy K., Lieba Faier, Michael J. Hathaway, Miyako Inoue, Shiho Satsuka, and Anna Tsing. 2009. ‘A New Form of Collaboration in Cultural Anthropology: Matsutake Worlds’. American Ethnologist 36 (2): 380–403.

[2] Ibid.

Get more stuff like this

in your inbox

Subscribe to our mailing list and get interesting stuff and updates to your email inbox.